Bonds! What are they good for? Equity Markets Lapping the one-year anniversary of the global pandemic, developed equity markets […]

The primary objective of the Bank of Canada (BOC) is to safeguard the purchasing power of Canada’s currency, with this accomplished by trying to keep the change in domestic prices low (but positive), stable and predictable.

Of course, focusing on keeping inflation stable means trying to balance out the risks to the outlook, and this means not just trying to prevent or mitigate economic downturns where weakness in demand creates disinflationary pressures, but also attempting to avoid situations where an economy overheats and sees price pressures intensify as too much money chases too few goods.

With this in mind, to say that the economic backdrop is providing a challenge for policymakers right now would seem to be an understatement.

Measures of economic growth are proving to be robust despite ongoing lockdowns, and the outlook is improving with every vaccination. Downside risks also remain elevated, however, as the pandemic is far from over, with persistent threats from variants and continued significant supply-side constraints weighing on overall activity.

Demand strengthening (underpinned by government income supports and accommodative monetary policy) at a time when supply chains globally are struggling to get back up to speed has resulted in rising indications that price pressures are starting to build. Add to that the impact of the consumer price data from one year ago being severely impacted by the onset of the pandemic, and recent 12-month overall inflation readings have surged to their highest levels in a decade.

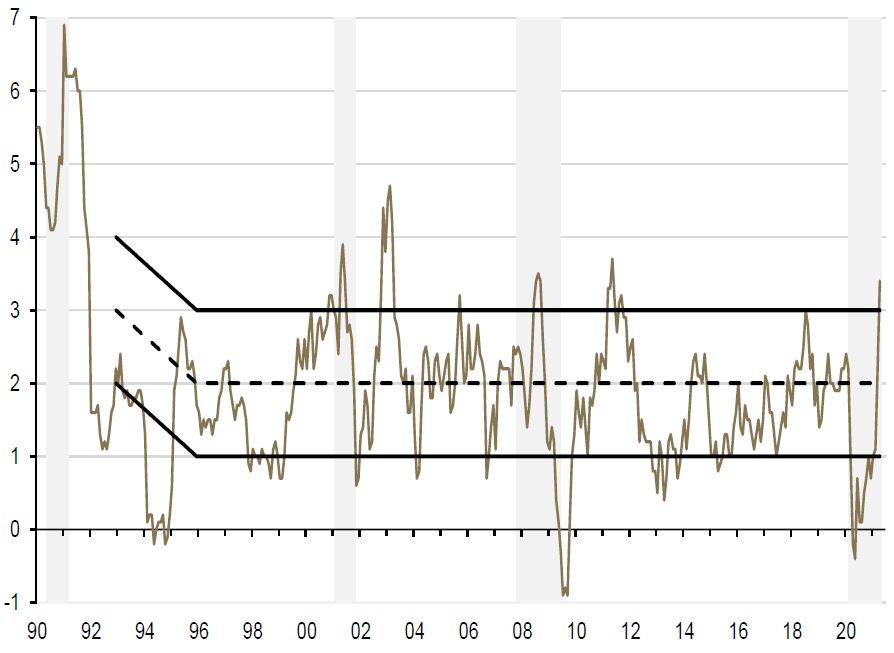

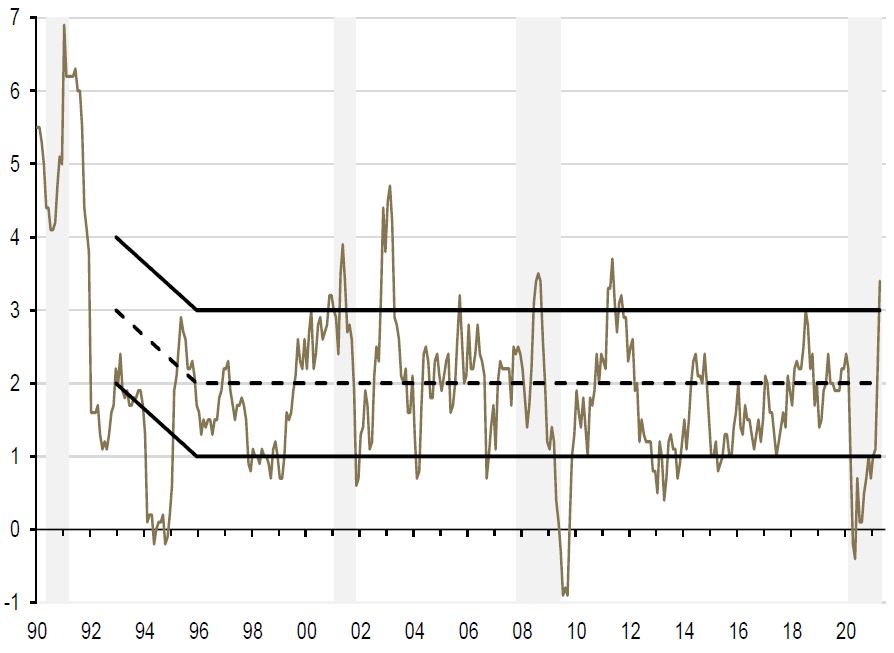

Canadian Consumer Price Index (Year-over-year percent change)

Shaded regions represent periods of US recession; solid black lines are top/bottom of Bank of Canada inflation target rage, dashed line is midpoint; data to April 30, 2021; source: Bloomberg, Guardian Capital

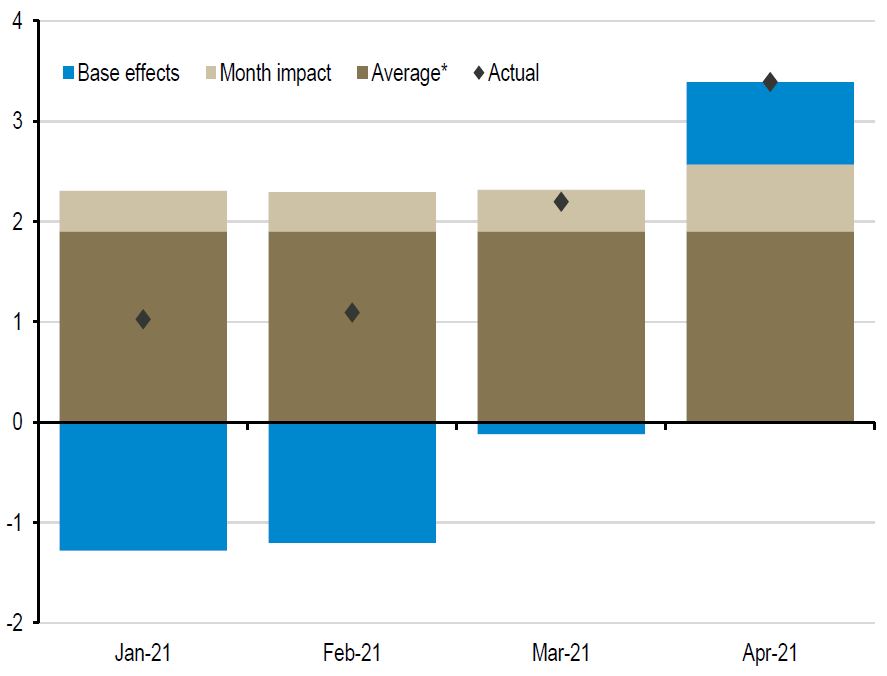

The “base effects”¹ due to the temporary abnormal weakness last year are not a big concern from a policymaking perspective, since they will eventually fall out of the year-over-year calculation. What does matter is that stronger-than-normal monthly increases are playing a notable role — as is the fact that the gains have been broad-based, with all major subcomponents in Canada, except food, alcohol and tobacco, posting much larger than normal increases in April; and more than half of the individual goods and services included in the Canadian Consumer Price Index having increased at a better than 2% annualized rate over the last three months (this has been less the case in the US, where the monthly strength has been the result of outsized gains in a few narrow subcomponents).

Decomposition of 12-month change in Canadian Consumer Price Index (Percentage points)

*The average changes for a given month over the 20 years prior to the pandemic; data to April 30, 2021; source: Bloomberg, Guardian Capital

Some of these pressures may well prove transitory — for example, those resulting from supply chain constraints tied to lockdown measures that will fade as restrictions are rolled back in the coming months and activity resumes at more normal levels — and the assumption from the BOC is that the uptick in inflation will prove temporary, with overall inflation expected to moderate through the end of this year.

Should this forecast come to fruition, it would provide the scope for a continued highly accommodative stance from the central bank to support the ongoing economic recovery — the resulting higher-growth, low-rate outlook would be constructive for corporate credit and could lead to a sustained bid from yield-hungry investors on any securities that offer added carry².

If, however, the inflationary pressures prove to be more persistent than assumed, that could put Canada’s monetary authority in a bit of a bind.

The BOC operates under a ‘flexible inflation targeting’ regime, where it aims to achieve inflation close to the midpoint of its targeted 1% to 3% range. Contrast this with the newly adopted “average inflation target” by the U.S. Federal Reserve System (FED) that permits it to accept above-target inflation to offset periods of below-target inflation (which have characterized much of the last decade), such that the long-term average is 2%.

While this framework gives the Canadian central bank some wiggle room in terms of tolerating inflation above 2% as the recovery gains traction and the pandemic approaches its endpoint, sustained firmness against an improving backdrop will put pressure on the BOC to do something so it does not lose its grip on the reins while adhering to its mandate.

Indeed, as it stands now, markets anticipate that the BOC will lead the way among major developed market central banks in lifting its policy rate from its effective lower bound, just as it already has acted as the first mover in beginning to taper its asset purchase program.

Overnight index swap-implied* year-ahead policy rate changes (Basis points)

*1-year forward overnight index swap rate minus current policy rate; data to May 28, 2021; source: Bloomberg, Guardian Capital

This is far from a sure thing, however, as the potential for a policy error looms large — removing policy stimulus too quickly risks choking off growth before it is able to get moving in earnest, while also negatively impacting financial markets; leaving policy too loose for too long will spur inflation and stoke asset price bubbles.

Policymakers have a delicate balancing act to manage in the coming months, and financial markets will scrutinize each incoming data point and every utterance from policymakers at the BOC to try and gauge on which side the coin will land.

The presence of policy uncertainty would seem to suggest that bond markets could be vulnerable in the coming months to headline shocks and bouts of volatility that have been increasingly sparse in the environment of persistent and abundant monetary accommodation. Add near-zero interest rates to the mix and investors are looking at an asymmetric risk profile in fixed income markets: very little compensation (yield) for undertaking significant risk. That would not only keep managing risk exposures at the forefront of portfolio management decisions—particularly sensitivities to higher interest rates and inflation—but could also create potential opportunities as knee-jerk selloffs would provide better entry points for active investors.