Summary It has now been seven months since the initial wave of COVID-19 caused the world to go on lockdown. […]

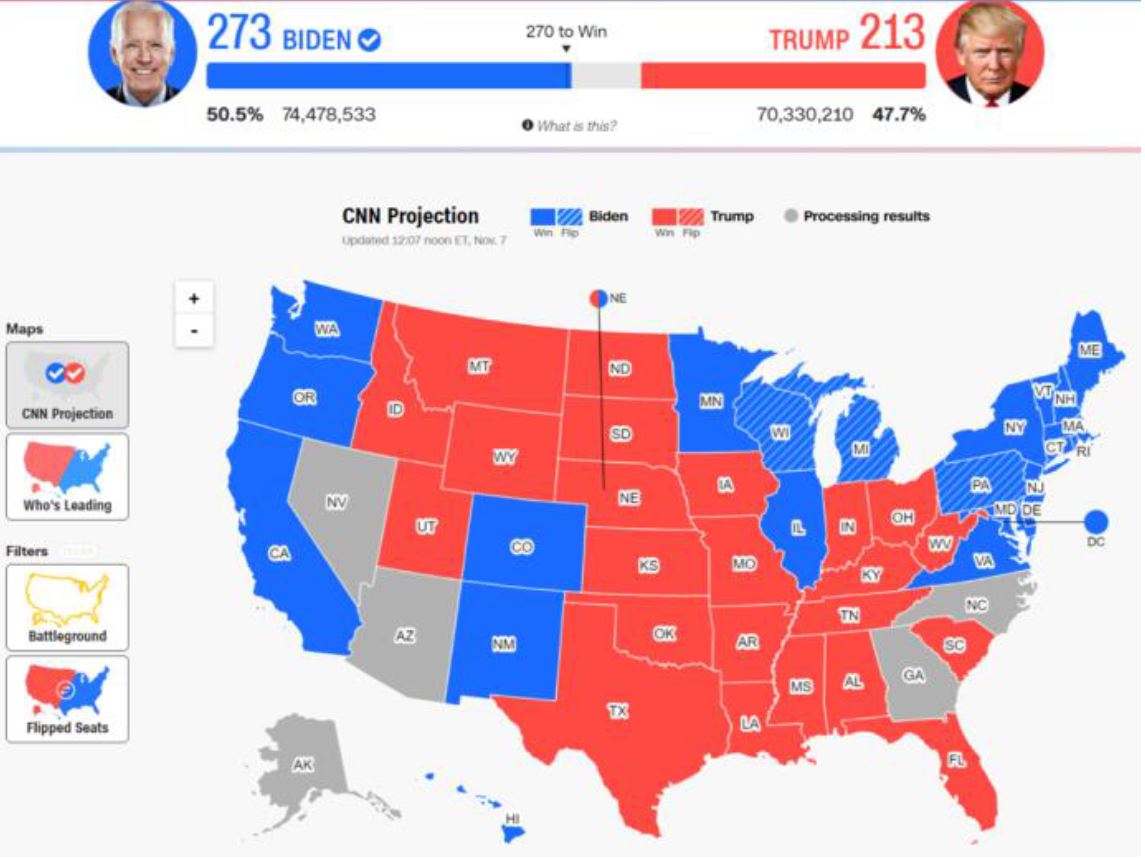

While there still are votes left to be counted (and the current President has now filed three lawsuits related to the counting, with threats of more to come), it appears as though there is a now clearer picture of the outcome of the 2020 US Election.

Thanks to the performance in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania (three key swing states that Democratic Presidential nominee Hillary Clinton lost in 2016; these states also happen to be ones that were restricted from counting mail-in/absentee ballots prior to Election Day and therefore have been delayed in turning out results), it looks as though Joe Biden will become the 46th President of the United States. The estimated win in Pennsylvania will be enough to push the former Vice President above the 270 Electoral Vote threshold. The margin of victory is much narrower than the pre-election polls were suggesting, but a win is still a win.

US Electoral College Map

Source: CNN, estimated results as at 12:07 pm EST on Nov 7, 2020

The potential for challenges from the Republican Party for some of the results at the state level remains. Still there is no evidence yet of any improprieties with the voting process anywhere and the margin of victory is wide enough to make recounts unwarranted. For example, a recount was done in Florida in 2000 when the gap between Bush and Gore was just 537 votes; the current margin in Pennsylvania is 34,414 votes.

Down-ballot, the expectations of a “blue wave” have not materialized. While the Democrats made some headway in the Senate, it appears the Republicans will retain the Upper Chamber of Congress (though there remains a small chance of an even split if the Democrats can take the both Republican-held seats in Georgia that appear to be heading toward a run-off). The Democrats are primed to retain power in the House of Representatives but they performed worse than anticipated, and are estimated to have lost seats even there.

The likelihood of a split Congress means that the hopes of substantial, large-scale public infrastructure investment and a significant COVID-19 relief bill are materially diminished — though, the recently re-elected and current Senate Majority Leader has stated that passing a pandemic stimulus package will be a priority for Congress before year-end.

As well, other major policy changes that were part of the Democratic platform will face difficulty getting through the Senate. That means that major changes related to policies on health care, personal and corporate income taxes, labour, climate, Green energy, Senate rules, courts and regulation are not likely to come to fruition in the 117th United States’ Congress’ two-year term.

Expectations of smaller government spending plans mean a lower anticipated growth trajectory for the world’s largest economy, but that is being countered in the notoriously change-averse marketplace by the anticipation of the status quo everywhere else. The absence of a tax increase is unambiguously positive for corporate profits, as are lower odds of tighter regulatory oversight for some of the most important areas of the market.

Add to that the potential for a more stable presence in the White House and a less hostile approach to foreign relations (while a strong position on China is likely to continue, the expectation is it will be more diplomatic and rely less on tariffs), and you have a political backdrop that is constructive for risk assets over the near term, and can largely explain the strength in equities this week. As well, there is a high conviction that a COVID-19 vaccine will come to market sooner rather than later, which could add more persistent and broad-based support to market sentiment into next year.

In the bond space, while the rally in government-issued securities since Election Day is open to interpretation (as a sign of investors being ‘spooked’ over the outlook in the absence of a large dose of fiscal stimulus), there are arguments in favour of an explanation that is much less dour.

Over the last month, bond yields have been moving higher against polls, showing a high probability of a Democratic sweep that would usher in a new era of debt-financed government spending. For example, the yield on the 10-year US Treasury note jumped from 0.70% on October 2 (the day that Donald Trump announced his positive COVID-19 diagnosis) to 0.90% on November 3 (Election Day).

Yields have fallen since November 3, reversing some, but not all, of the increases (the US 10-year yield closed at 0.81% on Friday) as markets have rethought not only the smaller potential inflationary impulse associated with the expectation of less public investment but, more importantly, the lower supply of debt expected to be issued by the US government.

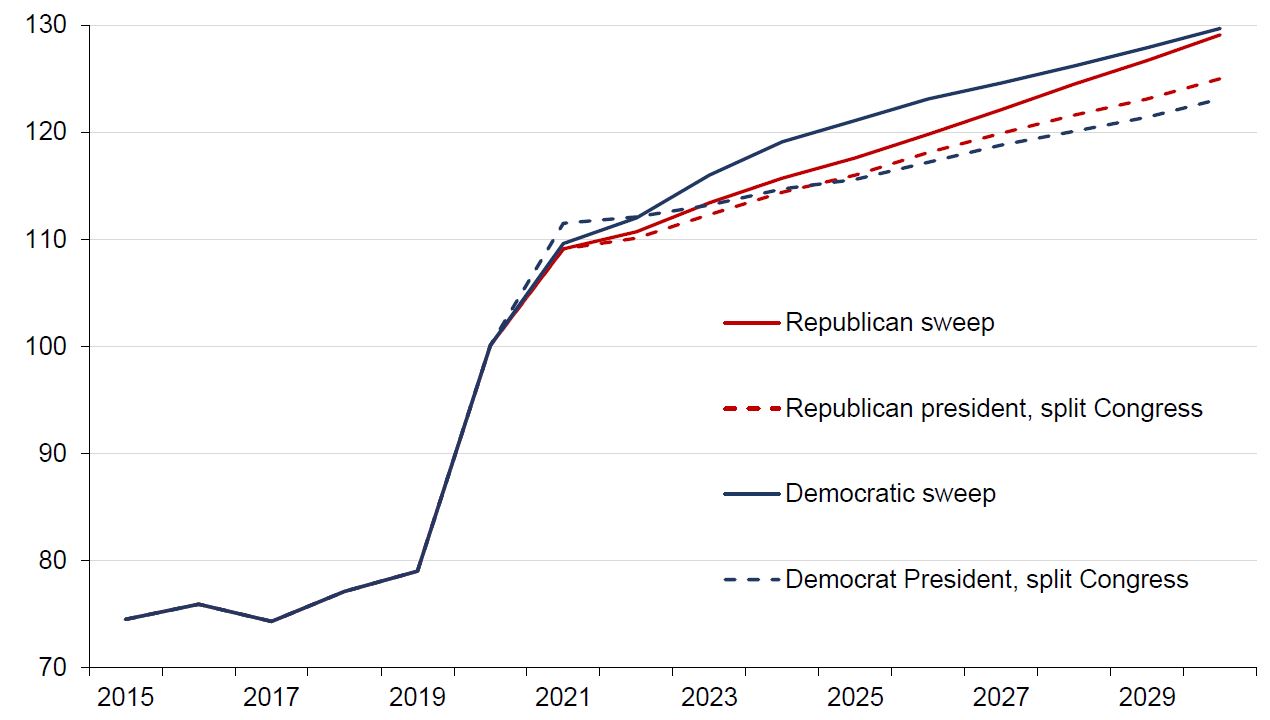

US Federal government debt (percent of nominal gross domestic product)

Source: Moody’s Analytics (The Macroeconomic Consequences: Trump versus Biden; 9/23/2020), US Bureau of Economic Analysis

For example, in their analysis of the candidates’ economic plans ahead of the election, Moody’s Analytics estimated that a Democratic president with a split Congress would result in the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio of all combinations in 10-years’ time — a difference of roughly US$3 trillion that would need to be issued by 2030, in comparison to the Democratic sweep scenario.

The bottom line is that there appears to be clarity on the US political front in much shorter order than was assumed earlier this week and the largest risks (namely, of a legitimately contested outcome) have not materialized.

Clearly, there remains plenty of risks, but moving past this key risk event, with the hope of greater policy certainty on the horizon, represents clearing a hurdle for investor sentiment through the end of the year.